(B.18)

RIVER, ROAD AND RAIL

Some Engineering Reminiscences

by Francis

Fox (Memb. Inst. Civil

Engineers) - John Murray, Albemarle St., London (1904)

Chapter I and part of Chapter II - reminiscences concerning his

father Sir Charles Fox.

CHAPTER I

INCIDENTS IN LIFE OF SIR CHARLES

FOX

|

|

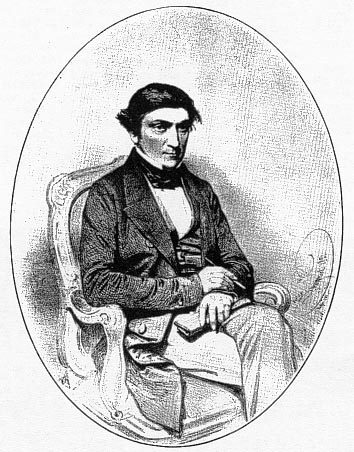

BEFORE giving an account

of some engineering works and experiences, it may be

interesting to place on record a few reminiscences of my

late father, Sir Charles Fox. He was born in the Wardwick,

Derby, in 1810, being a son of the leading physician and

surgeon in that town, and had as his tutor for some years

Mr. George Spencer, father of the late Herbert Spencer, the

political economist. My grandfather intended that his son

should follow his profession as a doctor, and consequently

he worked in the surgery for two years; but in 1831 his

keenness for railway engineering, which was then a new

profession, induced him to abandon medicine, and he left

home for Liverpool. He obtained employment with Messrs.

Fawcett, Preston & Co., and afterwards became associated

with the well-known Mr. Ericsson, of " Monitor " fame, who

was then designing one of the locomotives which eventually

competed at the celebrated Rainhill trials. On that occasion

my father drove the locomotive "The Novelty," which, but for

the fact that it blew a tube, would probably have been the

winner of the prize of £500.

For a time he took to

locomotive driving, just as people in these later days take

to driving motorcars, and was regularly employed for some

time on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in that

capacity : he had whilst there the trying experience of

being present when the director of that company, Mr.

Huskisson, was killed.

|

One dark winter's night he arrived in

Liverpool with a level-crossing gate hanging on to the buffers,

having, in the absence of signals in those days, run through the

level crossing whilst the gates were shut across the

railway.

It appears from a letter which I

possess, and of which a facsimile is given [Ed. not included

here], that Ericsson had his misfortunes, evidenced by the

fact that he found himself " in a fairly comfortable bailiff's house

in Liverpool," but nevertheless he lead sufficient humour to make a

pen-and-ink sketch of his window, showing the iron bars which

imprisoned him.

My father became a pupil of, and

afterwards assistant to, Mr. Robert Stephenson, who was then the

engineer of the London and Birmingham Railway, now the London and

North-Western.

Whilst engaged in the construction

of the Watford Tunnel in 1834, he received instructions to go to

Birmingham. He asked to be allowed to remain, for they were working

in very soft and dangerous ground ; but his request was declined, and

he was sent to Birmingham. He had not been gone more than a few days

when a message was received that the tunnel had fallen in, and eleven

men had been killed. He immediately hurried back, and found that

there was a panic on the spot. Up to this point is what nay father

himself told me, but a very old friend of mine further related that,

when the tunnel had fallen in and had produced this panic, my father

went to the works and said to the men, "That tunnel has to be put

through, cost what it will, and therefore I want you men to

volunteer." Not one of them would do so. "Very well," he said, "I

will do it" ; and he got into the bucket, and was just about to be

lowered down the shaft, when the ganger, using language more strong

than elegant, said he "would not see the master killed alone." He

went down with him, and these two finished the length through the

dangerous ground, after which the men

returned to

work.

In 1837 Herbert Spencer entered the

office at Camden Town as an assistant engineer to my father, and it

was during this time that my father designed the present roof over

Euston Station, the first of the kind ever made. He afterwards

designed or built the large iron roofs of New Street Station in

Birmingham, of the Great Western Railway at Paddington, and others at

Waterloo Station, York, and elsewhere.

An amusing episode took place

during his lifetime in connection with the completion of a certain

railway in Ireland. The company fixed a day for the opening of the

railway, notwithstanding a warning given by the contractor that he

would not allow it to take place unless his final account were

previously paid. The company ignored the contractor, invited the

mayor of the city to start the train, had a battery of artillery to

fire a salute, and filled the special train with their friends,

intending to take them to the other end of the railway, some twenty

miles, where a luncheon had been provided. The mayor waved his green

silk flag, the band struck tip, the artillery fired a salute

(bringing down the glass of the roof), and the train started, but

only to be brought to a standstill by a man on the line waving his

arms and shouting that the rock cutting had fallen in. The fact was,

some hundred tons or more of rock had been blown on to the railway by

a gunpowder blast, thus effectually blocking the line and rendering

it impossible for the train to proceed.

The chairman was furious, and

wished to arrest everybody concerned; and the visitors not being able

to get to the other end of the line, the luncheon was duly consumed

by the navvies. Late in the afternoon it was remembered that a full

account of the opening, with all the speeches, had already been sent

to the newspapers. The secretary telegraphed to stop it being

inserted, but the answer carne back, "Too late-gone to press," the

result being that a full account of the ceremony appeared next day in

Dublin, although it had not taken place.

Here let me give an

illustration of the inconveniences imposed on busy men by summoning

them unnecessarily to courts of law.

On a certain occasion, whilst

sitting in his office in Spring Gardens, a man walked into my

father's room, and served a "subpoena" upon him, requiring his

attendance at the assizes. He protested that he knew nothing of the

case, but the man was insolent, and simply said, " To Chelmsford

you'll go."

To Chelmsford therefore he went,

and in due course was called, and sworn, to give evidence. He

addressed the judge as follows: "My lord, am I not entitled to my fee

and expenses before I give evidence ? "

"Oh, certainly !"

The counsel said, "Sir Charles, you

need not be uneasy about that ; I will see you are paid."

But he said that would not satisfy

him ; if they insisted upon calling him as a witness, they must pay

him there and then.

A little delay occurred before the

necessary funds were produced; but having received them, the counsel,

who was evidently nettled, said, "And now, Sir Charles, having wasted

the time of the learned judge, of the jury, and the whole court,

perhaps you will tell his lordship all you know of this

case."

"Well, I know nothing," said Sir

Charles, "for you have called the wrong man " ; and having bowed to

the judge, he left the court.

Amongst the many guests at my

father's house in those days was the dear old Professor, Michael

Faraday; and we had the privilege of attending his lectures at the

Royal Institution. He, like all other lecturers, occasionally failed

in his experiments; but, when this occurred, not only did he take the

disappointment with the greatest good-humour, but he at once turned

it to such good result, by investigating the cause of the failure,

that we almost preferred that his experiments should occasionally

fail.

He used to play with us children,

and many a time he was to be seen rolling on the drawing-room floor

in a Christmas romp, or indulging in "hide-and-seek."

|

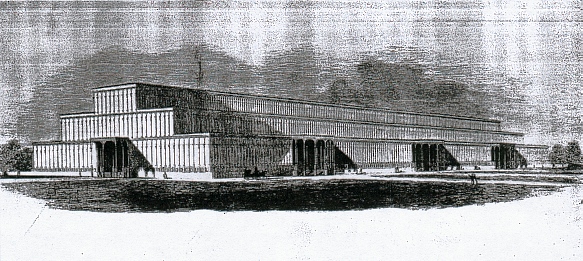

In the autumn of 1850 my

father received the order for the erection of the Great

Exhibition of 1851. The idea of a building of glass and iron

was due to Sir Joseph Paxton, but the original design was

not altogether a pleasing one, consisting as it did of a

plain rectangular building.

When, however, it is

remembered that no less than two hundred and twenty

competitive designs were submitted for the building, it is a

matter for congratulation that so light and fairylike a

construction was the result.

|

|

It is impossible to give the names of

all those connected with this great work, but amongst others appear

those of Cubitt, Barry, Owen Jones, Digby Wyatt, Cowper, Cooper, and

many others.

From the commencement it was

decided that the building in all its various dimensions, the length,

width, and height, should be multiples of 24, the girders being 24

ft., 48 ft., or 72 ft., and so arranged that any columns or girders

taken haphazard should be interchangeable. In fact, the system of

standardization, at last being adopted in Great Britain and the

Colonies, was carried to a high state of perfection in this

structure.

My father and his then partner, Mr.

John Henderson, suggested the introduction of the arched transept to

cover the large elm trees which proved to be the great feature of the

building. The contract was accepted late in 1850, and the Exhibition

was to be opened in May, 1851 ; but, owing to the extreme novelty of

the design, it was considered by most people that it was impossible

to complete it in the time. My father had great confidence in cast

iron if properly designed, and he became known as the "Cast-iron

Man." No one but he was able to design the building as regards its

details, and therefore upon him, personally, devolved the duty of

drawing nearly everything, even to the most minute particulars.

Eighteen hours a day was he at work at the drawing-board, and, so

soon as a plan was pencilled in, he sent it to the drawing-office to

be traced and put in hand in the pattern shop.

Although quite a boy, I visited the

building during its erection nearly every day, and on several

occasions with the old Duke of Wellington. He was almost the only man

who thought the work would be completed in time, and he used to pat

my father on the shoulder, saying, "You'll do it yet."

Several amusing incidents occurred

during the erection. One of the large trees in the park came exactly

in the way, and would have effectually prevented the glass end of the

transept being fixed. My father applied to the authorities for

permission to cut it down, although two other trees were arranged to

be enclosed in the building. No consent could be obtained, and a

meeting was therefore arranged on the spot, when all who were

interested attended, but the leading official ordered that the tree

must not be touched. My father turned to his foreman and said, "John,

you hear what this gentleman says ; on no account must this tree be

cut down.''

" All right, sir."

That night the tree was felled,

and, when once down, could not be reinstated. A row of young trees

also interfered with the building, and as no official consent could

be obtained for their removal, private arrangements were made for

shifting them a short distance. All the joiners' benches were placed

near them, and the ground speedily covered with a foot or more of

shavings to prevent the movement of the soil being noticeable, and

then one night all these trees were transplanted, being removed in a

line the necessary distance to clear the building; but, as the

Ordnance maps showed all these trees, the authorities were at a loss

to understand how it was they were so inaccurately indicated on the

plans.

An old wooden pump, for the removal

of which permission was asked, an undertaking being given to replace

it after the Exhibition was closed, was not allowed to be touched;

and so it projected through a hole in the floor into the building

itself; during the whole time the Exhibition was open to the

public.

When the structure was well

advanced, the glazing had to be commenced, and, so soon as any of it

was fixed, it was essential that the whole should be completed as

quickly as possible before any strong wind came, for, should half or

three-quarters be glazed, there was always serious risk of the glass

being blown out. Unfortunately this very thing happened, in spite of

all care ; a very severe gale came on just at this critical time, and

the effect was much the same as when one holds a thin paper bag with

its mouth open towards a gale. The glass was blown out almost by the

acre, and heavy loss was occasioned.

The structure was approaching

completion when some one started the theory that, as it was intended

to have music at the opening, an accident would be caused by the

vibration of sound causing the glass to shake. Each pane of glass

would take up its own responding note, and would consequently vibrate

with such violence that it was predicted "the glass would come down

in showers." It was therefore necessary to try the experiment so as

to allay any fears in the public mind.

On a particular day, whilst the

work was in full operation, hammering going on in every part of the

building, Herr Reichardt, the well known tenor, began to sing at one

end of the building. Gradually the hammering ceased, and, as the song

proceeded, silence prevailed amidst the whole audience of attentive

workers, and at its close it was received with loud

applause.

The full orchestra was then tried,

and all the bass pipes of the organ groaned aloud in thorough

discord, in the effort to shake out the glass, but not a pane moved,

nor even responded. The Government authorities were invited to test

the building in any way they thought fit, and it was in consequence

of this that the Sappers and Miners (now the Royal Engineers) were

told off to march "at the double" over a platform erected upon the

girders.

The rhyme which I add as an

appendix, based upon

"This is the house that Jack built," appeared

in 1851, and is worth recording.

I remember a letter about this time

coming to my father addressed in the following somewhat vague manner:

"To the bilder, what is bilding the bilding in I. Park" ; but the

Post Office authorities, with their usual ability, solved the

problem, and the letter reached its destination.

A photograph of the opening, by Her

Majesty Queen Victoria, of the Great Exhibition on May 1st, 1851, is

given, in which the Prince of Wales, now our King Edward VII, known

as "The Peacemaker," is shown standing on her right hand: my father

and Sir Joseph Paxton (the two left-hand figures in front with silk

stockings) standing side by side.

When the building was removed by my

father to Sydenham, to its present exposed position, it was again

predicted that it would not stand - in fact, the leading authority on

wind pressures of that day stated in public that, under the action of

gusts of wind, "he could not entertain any belief that the building

would endure for a long time." It is a curious fact that, if at any

time a pane of glass is blown in, it is almost invariably on the

leeward, or protected side.

|

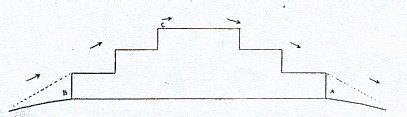

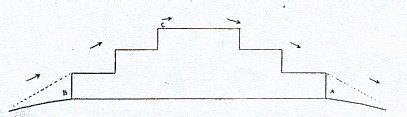

Assuming that the wind is

blowing in the direction of the arrows, it occasionally

happens, in very strong gales, that a pane of glass, which

probably has loosened, blows in. In such cases it is always

about the point A, and blown inwards ; and it is

observed that no severe wind is felt at B, on the face of

the building towards the wind.

|

|

The explanation of this is, that a

triangular mass of quiescent air, as shown by the dotted lines,

causes the gale to be deflected upwards and over the building; at the

point C the full effect is felt. The wind then passing down clear of

the building, leaves another mass of quiescent air at A ; but this is

slightly rarified, and its barometrical pressure reduced by the drag

of the gale. When a momentary lull occurs in the storm, this air

regains its full barometrical pressure, and the increase is

immediately felt by any loose glass at A.

|

|

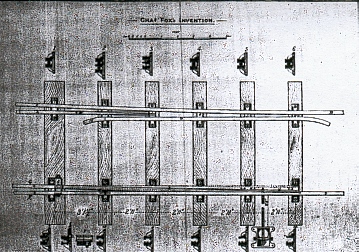

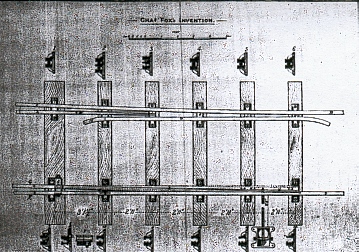

My father has left his

mark on every railway in the world ; amongst his many

inventions was the switch, which is now in universal use.

Prior to this the ordinary sliding rail, as used by

contractors today, was the only device ; but it had this

great disadvantage, that, if a train were shunted when the

rail had been moved, it ran off the metals and was derailed

; whereas with "Fox's patent switch" the train remains safe

on the line.

A photograph of his

original design, dated 1832, is given, in which only one

"tongue" to the switch was proposed.

|

He was also the first engineer to

adopt the cast-iron cylinder, or caisson, for the construction of

bridge foundations in rivers, which is now of world-wide

application.

One thing which strongly impressed

me about my father in connection with his position as master towards

his men was this : he laid it down as a maxim that he would never

dismiss a man for an accident, unless it was due to downright

carelessness. He used to say that the man, having been educated up to

that point at his expense, would never commit the same blunder again,

and consequently he was of more value to him than others. If this

policy were more generally adopted, many a really valuable workman

would be saved from social wreck, and the masters would be greatly

benefited.

After many years of arduous and

useful work my father died at Blackheath on June 24th, 1874, at the

comparatively early age of sixty-four, his decease having been unduly

accelerated by the effect of a serious accident.

CHAPTER II

EARLY REMINISCENCES

MY first introduction to

engineering was of a somewhat startling character, for on one of my

visits to see the construction of the Great Exhibition of 1851 in

Hyde Park, as already described, it being a very hot day, I sat down

on a small seat, and fell fast asleep. It so happened this was what

is known as a "boatswain's chair," used by the workmen in the

erection of the ironwork, and some of the men amused themselves by

tying me into it, and then hauling me up to the roof. When I awoke I

was hanging in mid-air, much to their amusement, but somewhat to my

own alarm.

It was on one of these visits that

an incident occurred which impressed itself deeply on my mind, and

the absolute truth of which I see as I grow older. A bricklayer, one

of many, was engaged in building a brick pier about three feet square

and six to eight feet in height, and in his haste or carelessness he

built it out of the perpendicular ; it leant over to one side. My

father, who was erecting the Exhibition, saw this with his ever-quick

eye, and was walking up to the man, when he dropped his trowel, came

to meet him, touched his cap, and said, "Please, sir, don't be hard

on a fellow." "Well, you blockhead, why don't you build your work

upright ?" And he replied, with great truth, "Well, sir, you see,

there are so many slants, but there's only one

perpendicular."

And so it is all through life. How

many wrong ways there are of doing a thing, but only one right one!

...........

Top

of page

; Go

to Sir Charles Fox-notes ;

Return

to Background Index

20/03/02 Last Updated

23/03/02;25/1/04(sp)